In Part 1 of the series The Politics of Distraction, Steve Sharp identified the UN Summit in Glasgow last November as the high-water mark of Pacific climate diplomacy. Despite Pacific diplomats proving themselves climate warriors abroad, ‘climate action’ at home has fallen short of island states’ own high ambitions for environmental stewardship, endorsed by Pacific Island Forum members in Suva early this month. In this second part of the series, he turns attention back onto degraded Pacific environments that have little to do with emissions targets or climate inaction by foreign governments.

The persuasive industries that support international climate diplomacy are what make grand alliances appear credible to international audiences. Their techniques sharpen and simplify the message and concentrate its narrative power at crucial moments of negotiation. And they profoundly shape climate politics, which is full of contradictions and distorted emphases. Take, for example, how campaigners represented Pacific mining and forestry in relation to ‘climate action’.

In fact, it is hard to find any reference to these two critical industries in the campaign materials of Pacific activists leading up to COP26. And to continue the trend, their co-campaigners in Australia barely mention the environmental destruction wrought by miners and loggers as obstacles to achieving UN targets – impacts which lie at the heart of Pacific states’ own obligations to abate emissions.

Firstly, mining is very energy-intensive with a growing carbon footprint. Due mainly to fossil fuel consumption, mining activity accounts for 4-7% of total global greenhouse gas emissions.

Papua New Guinea has an established mining industry and the Solomon Islands has an emerging one, generating significant revenue for both economies. Mines also destroy forests and have a long history in Melanesia of environmental pollution with all its attendant curses: Freeport, Panguna, Ok Tedi, Lihir, Porgera, Ramu, LNG project and more recently in the Solomon Islands, bauxite mining on Rennell Island, the island’s eastern part inscribed on UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger.

If mineral-rich Pacific states want to power their economies by trading their natural resources with resource-hungry buyers abroad, that is their sovereign choice. But recent data suggests exporters are economically disadvantaged by this choice, leaving them with degraded environments that make them even more vulnerable to the vagaries of climate change. This is true of both mining and forestry.

More historical data from 2016 on the PNG forestry sector indicate that unequal exchange relations are embedded through transfer pricing ‘resulting in a loss of tax revenue that may exceed $100 million per year’.

In relation to mining, the warning signs were there. Six years ago, the case for how ill-prepared the Solomon Islands was to run a minerals-based economy was thoroughly canvassed in a paper by Graham Baines. His lack of confidence was based on the history of forest management under successive governments.

Take the Chinese-owned bauxite mine on Rennell as a case in point. The local manager of another foreign miner in the Solomons that fell out of favour with regulators, had this to say in 2019 about the regulation of the nascent industry:

‘There is great disorder in the mining industry due to non-compliance to the mining and environmental laws by companies like Bintan Mining Company and MMERE’s [Ministry of Mines] paralysis in disciplining such companies for their reckless behaviour.’

Bintan is the miner that hired the carrier which in February 2019 hit a reef in a storm while loading bauxite and spilled 300 tonnes of oil onto the reef. And later that year 5000 tonnes of its bauxite export cargo fell off a barge into the bay. While the loss from the first spill has been quantified at AUD$50 million, mining itself has denuded Rennell’s garden plots with long-term impacts on the island’s food security. This points to a looming crisis that is the result of resource development policies, not climate change. As SIBC put it: ‘While climate change continues to threaten the island’s lives, human-made disasters are just as costly, placing people’s livelihoods at stake.’

Those policies are often disputed, and sometimes investigated but are usually opaque. Like when Bintan’s contractor and mine operator – APID – a logging company – was granted a mining licence in 2014. After the two marine disasters cited above, Bintan not only retained the right to mine bauxite on Rennell but was granted prospecting licences in another province.

Could the double whammy of logging and mining on small islands like Rennell make them uninhabitable and add to the pressure for internal relocation now playing out in larger provinces?

And if so, why is mismanagement of resource extraction not given the same status as sea level rise in the memos of climate bureaucrats? Is it because it is the child of national policy failures and cannot be blamed entirely on greedy foreigners?

Forest plunder a security issue

On the 25th August 2020, the PNG Post-Courier published an editorial that commented on a recent taskforce investigation into logging operations in Northern Province, agreeing that ‘companies who have no respect for the law of PNG and habitually breach them must be banned from operating in PNG’. It was referring to – among other things – the escape by aircraft of 16 foreign workers before the taskforce arrived at their logging camp. This must be, the newspaper guessed, ‘the tip of the iceberg’.

‘We must change the image of PNG as an easily penetrable nation that can be used, abused and exploited by greedy corporate entities.’ These strong words from PNG’s leading daily read like a textbook case of non-traditional security threats: foreign workers illegally breaching PNG’s borders, unregistered vehicles found at the logging site, police hired by loggers to secure their sites, bribes and gifts given to metropolitan officials, habitual lawbreakers left untouched, resource security imperilled and so on.

But ironically, the substance of the editorial accusation could have been credibly made at any time during PNG’s decades-long history of timber piracy. And as is so often the case in stories of Pacific resource plunder, none of the individuals responsible are actually named.

In the Solomon Islands, the deals remain shadowy, but in PNG, there is an abundance of official documentation, court judgments and inquiry reports to infer a permanent state of lawlessness in environmental management.

Take the historical example of the SABL leases, a monumental land grab with long-lasting impacts on landowner rights, despite most of the scheme’s leases being declared illegal in 2014. Customary land and other rights continued to be violated in what the Oakland Institute has called ‘a multilayered tragedy of the betrayal of people’s constitutional protections and the loss of cultural heritage and land for millions of Papua New Guineans.’

And yet Pacific climate activists drawn from the urban elites pay lip-service to ‘indigenous people’ who are ‘especially vulnerable’ to climate change without mentioning the rampant violation of rights that brings immediate and often irrevocable changes to their physical environments across the region.

Although all countries participate in the rituals of climate summitry, the spectacle of international cooperation obscures the main game of money politics which plays out at the national and sub-national levels.

Enhance timber legality

Under the UN framework convention, Papua New Guinea – like all countries – is required to report its national efforts to reduce greenhouse emissions and how state agencies intend to meet targets within specific time frames. These reports are known as intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs) or NDCs.

The PNG INDC report in 2020 addresses a source of emissions known as Land Use & Land Use Change & Forestry or LULUCF. This category includes commercial logging for export but also the conversion of forest to agriculture. The report commits PNG to reduce areas subject to deforestation (conversion) and forest degradation (logging) by 25% annually below their 2015 level by 2030. This equates, the report says, to a yearly reduction in degradation of 43,000 ha until the end of the decade. This will be achieved through a range of measures like the REDD+ scheme and another referred to as ‘enhancement of timber legality’.

If the latter is a clumsy way of saying ‘enforce the law’, there is plenty of evidence to doubt the capacity of government agencies to do so, and therefore, make meaningful predictions about what can be achieved in 8 years’ time.

Rampant illegality is one reason to doubt these formal projections will be met. But there is also the track record of previous global commitments. In 2014, 39 countries signed the New York Declaration on Forests pledging to halve deforestation by 2020.

But tree cover loss (13.8%) and primary forest loss (19.3%) increased by these significant margins. Another announcement heralded in Glasgow was a pledge by a much larger number of countries with stewardship over 90% of the world’s forests to ‘halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation’ by 2030.

PNG is one of the countries to sign on in Glasgow but its record to date does not inspire confidence that it will become a success story in 2030: it lost 72% of its primary tropical forest from 2010-2014 to 2016-2020.

In any event, the 2014 and 2021 commitments were voluntary – outside of the UN Framework Convention and therefore, are assured to receive less attention and scrutiny than binding emission targets forged in Paris. What real-world impacts are these declarations really having in signatory countries? If the answer is not much, then why make them in the first place? Because they have symbolic value along with high visibility and global reach? Climate politics, not climate action.

Further emphasising how national sovereign laws in the Pacific can be treated as ‘voluntary’, a 2018 report examined a range of logging project types that account for 85% of PNG’s log exports and found them all to contain legal violations. It concluded that any end-product purchaser wanting to avoid illegally sourced timber should consider all PNG timber exports ‘high-risk’.

But this assumes that consumers of timber products have some way of knowing the origin of their purchases. In the case of PNG, almost all log exports go to China which manufactures products sold to buyers worldwide. Large end-use importers like the EU and the United States have regulations banning imports made from illegally sourced timber.

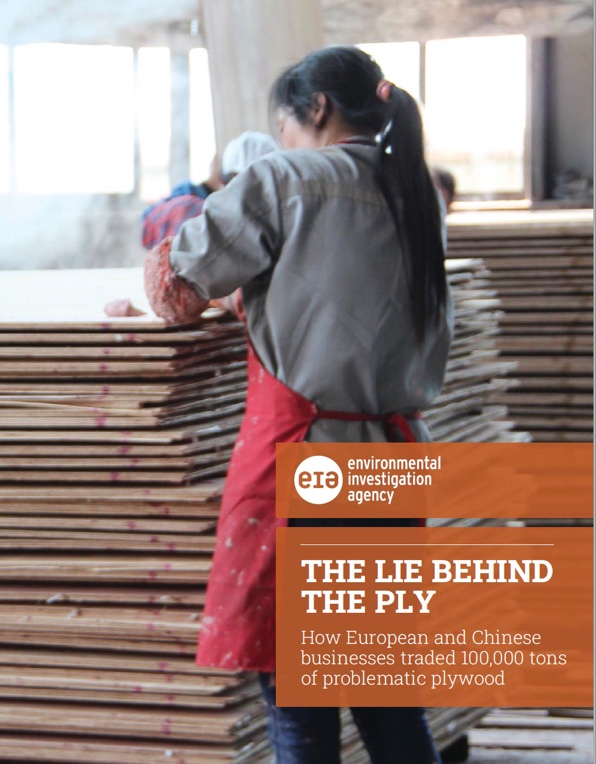

An investigation released last June documents how European buyers imported plywood from a Chinese state-owned exporter for several years. This plywood was fraudulently labelled as originating from a single certified (clean) source in the Solomon Islands. More likely, Environmental Investigation Agency argues, 95% of the plywood in question came from sources in PNG and Solomons considered high-risk under European law.

This is relevant to abatement efforts by responsible agencies in the two Melanesian countries and to whether their UN commitments to reduce forest degradation will amount to anything more than a bureaucratic smokescreen. Legal enforcement will require more than an aid project in the context of contaminated supply chains that have been fooling European consumers for years.

It is admirable and far-sighted for Pacific Island Forum member states to endorse a vision that takes into account future generations. But the region faces a crisis of legal enforcement in extractive industries now whose legacy may prove as irreversible as the warming oceans and rising sea levels so lamented by its global climate campaigners.